Music for self-flagellation: a Lenten Playlist

Gregorio Allegri: Miserere Mei – Psalm 51 was supposedly written by David after he had slept with another man’s wife. Even if you’re not an adulterer yourself, you can feel the heavy weight of regret in Allegri‘s famous setting of this text.

Herbert Howells: Like as the Hart – Dated April 1941, legend* has it that this anthem was written while the Nazis were bombing London. When I hear it, I imagine Howells crouching in fear in the corner of a dark house, listening to the explosions outside. He’s trying to calm his brain and find some peace. He dreams up music that is misty and serene, and tries to remember a prayer or a psalm to say. Psalm 42 comes to mind: a deer, thirsting for a stream of water. The beginning and ending sections feels unsettled and timeless; the middle section is full of stress and suffering.

*the legend probably isn’t true, since the work lists Cheltenham as the place it was composed – nearly 100 miles away from London. But it creates such a powerful image for this piece!

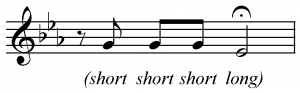

Johann Sebastian Bach: Cantata 38 “Aus tiefer Noth” – “Out of the depths I cry to you O God.” This piece is based on Martin Luther’s hymn setting of Psalm 130, another popular penitential psalm (P.P.P. – is that even a thing?). Bach magnifies it into a short masterwork. The final chorus begins on the highly unstable V42 chord (nerd alert!) – inconceivable!

Thomas Morley: Nolo Mortem Peccatoris – A contemporary of Shakespeare, Morley is best known for his madrigals. This sweet little devotional song sets an imagined prayer of Jesus before his arrest, using both Latin and English.

Gerald Finzi: Lo, the Full, Final Sacrifice – This festal anthem is a hymn to the Eucharist. Many prefer this to be sung during Eastertide, I consider it a Lenten piece because of its association with the Last Supper, plus the overall mood of the music: dark and passionate. And, it is one of two anthems I know that use the word “pelican.” (The other anthem that uses the word “pelican” is The Weasel Cantata, which claims to be the only anthem on the dietary laws of Leviticus.)

Giovanni Pergolesi: Stabat Mater – The Stabat Mater is a devotional that envisions Mary at the foot of the cross, watching her son die. The video below is only the first and last movements of a twelve movement work. Like most composers before Beethoven, Pergolesi probably didn’t compose this so he himself could become immortal, so there are some great movements that are great, and some that are … okay. We’ll skip to the best stuff for this one.

John Sanders: The Reproaches for Good Friday – The Reproaches are a set of devotional responses which originated in the Medieval era. The text is written in first person from the perspective of Jesus, who compares instances of God’s grace from the Old Testament to the cruelty of his crucifixion. No musical setting of this text is more powerful than Sanders‘.

Joel Thompson: Seven Last Words of the Unarmed – Another Lenten devotion is known as the Seven Last Words (sayings) of Christ. I’ll be honest and say I’m not really a fan of any of the settings I’ve heard. However, this new work by Joel Thompson is really powerful. Instead of the words of Jesus, Thompson sets the last words uttered by unarmed victims of police brutality. It’s chilling to hear.

Johann Sebastian Bach: Mache dich, mein Herze, rein – I guess I should end on a positive note, for those of you who like happy endings (as for me, give me a miserable ending every time!) This aria is from Bach’s setting of the Passion from the book of Matthew, and is sung just after Jesus dies, and provides a moment of respite from the very turbulent and emotional drama of the crucifixion.

Recent Comments