Why do we enjoy music?

read PART I of this post: Why do we make music?

Why do we enjoy music? And why are some pieces more likable than others? It’s a big question for a single blog post. I’ll do my best to be as clear and concise as possible!

Take a look at this video:

Why is this fun for us to watch? Would a simpler-minded animal enjoy this as much as humans do? Many YouTube videos of dominoes (and other physical events) are described as “satisfying” – why satisfying?

I start with this video because ultimately it is meaningless (like music?) – the domino build has no purpose other than to be destroyed. And once the chain reaction starts, we want to watch until the end. The pleasure we find has to do with expectation and fulfillment. Through our understanding of the physical world, we know that if you push the first block, it will knock down the next, and the next, etc. But why is it fulfilling to watch what we already know will happen?

Our brains are constantly working to predict what will happen next in the world, and many of our emotions are tied directly to our predictions. Consider a common scenario: the delicious, cheesy aroma of a pizza reaches your nose. You predict that you’ll soon be eating pizza, and if that expectation is fulfilled, you’ll be fat and happy. If, on the other hand, the expectation that you’ll be eating pizza is NOT fulfilled, you might react in a number of ways: Anger (the pizza is not for you to eat!), Curiosity (it turns out it’s not a pizza – what could be making that smell?), or Delight (it’s not a pizza, it’s a Stromboli, even better!)

Part of the pleasure of music comes from a combination of knowing AND not knowing what is coming next – and I should mention that this applies to any style or genre of music. We have expectations of sound (timbre), harmony, melody, and rhythm from any music we listen to. Whether or not you are aware of it, your brain has organized these musical qualities so that you can listen to a few seconds of any song/piece and instantly categorize it in a way that best suites your needs.

When you hear the opening chords of your favorite song, your ears perk up, and you get ready to dance and sing. Your body recognizes the sounds of the music, and identifies them as something familiar, known, and loved.

But consider your reaction when your expectation is shattered by an unwanted alteration.

Disaster.

This is a macro-example of expectation and fulfilment in music. But our enjoyment of music is based on this same principle on a subtle scale – so subtle that it’s possible you’re only unconsciously aware of it. Consider something as simple as the “ode to joy” theme. Hearing the first phrase of this hymn, a number of expectations are set:

Whether or not we know it, we now have an expectation of harmony (D major or one of its close relatives), rhythm (4/4 time of mostly quarter notes, one dotted near the end), and melody (goes up, goes down, goes up, goes down.) The music then continues:

The first three measures are identical to the one above! Expectation fulfilled. The last measure is slightly adapted to bring the phrase to a more solid conclusion. Expectation not met, but perhaps more fulfilling this way (it’s Stromboli!) (or perhaps, it was the first phrase which didn’t meet our expectation of a solid conclusion, and the second which did fulfill the expectation. Or maybe both at the same time, in different ways.)

Then comes this phrase, which uses a different set of harmonies, wider melodic range, and much more rhythmic variety:

So this is new material – where did it come from, and where are we going? Thankfully, before we start to lose our composure, we get a return of the initial phrase, concluding in the more fulfilling way:

This might seem a little far-fetched, but I believe this series of expectations and fulfillments (denied and delivered) are what drive our love of music – classical or popular. If you’re not yet convinced, let’s try pushing expectation and fulfillment to their extremes. What if our expectation is ALWAYS fulfilled, and virtually nothing is new?

Maybe at first it’s exciting because you recognize it (or equally exciting because you don’t recognize it), but after a while, it can get dull. After hearing only two pitches for the first few minutes, the unexpected third pitch sounds like an atomic bomb. On the other hand, when nothing is predictable …

… our attention is lost quickly because we have no expectations, and therefore nothing to fulfill. In this piece, the vocal melody is built on large leaps, instead of steps – definitely not the common expectation for a vocal melody. The harmony is not based on triads, and the rhythm doesn’t fit into the clean-cut measures that we expect in nearly all other music.

So we need both a set of musical rules that we accept as normal, and a composer who is willing to work within those rules, bending and breaking them at just the right moments, from micro to macro levels. What is especially interesting about this is that, even when we know how the composer is going to break the rules, it still excites us. We also might use this to consider our reactions when we dislike music – can we back up our distaste with concrete complaints or are we just lacking knowledge of a different style’s musical rules?

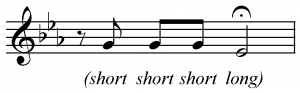

I want to end with the iconic 5th symphony of Beethoven, because both the primary theme is built on a short, easily recognizable 4-note motif:

After just a measure, we have very clear expectation. But Beethoven is able to craft this simple idea in new ways, over and over again, keeping our attention. We know what we expect, but are constantly delighted in the different ways the two motifs are presented. Even when we know this piece well, our brains stay in a state of delightful surprise.

Recent Comments